As stated in the previous section, I am not advocating for fan studies to be recognized by and integrated into the canon. While being labeled as a canonical genre would certainly expand fan studies’ critical and academic reach and would allow it to be incorporated into university curriculums on a large scale, it is not what I am arguing. Within the scope of this project, I argue that the canon is an ISA that continues to interpellate scholars and fans of longstanding canonical genres while systemically excluding popular and other noncanonical genres like fan studies. The problem is not that the canon is operates as an ISA, but that the types of people that the canon is hailing possess ideologies that suppress marginalized voices on the level of both the author and the reader. Louis Althusser defines ISAs as “a certain number of realities which present themselves to the immediate observer in the form of distinct and specialized institutions” that attract people who already prescribe to the ideologies that a particular ISA perpetuates (79). To put this another way, an ISA becomes an ISA by having certain ideologies and the social standing to project them onto people.

“[W]orks cannot become canonical unless they are seen to endorse the hegemonic or ideological values of social groups” while “noncanonical works can be seen to express values which are transgressive, subversive, and antihegemonic”

John Guillory

ISAs cannot function on ideology alone. While ideologies are a critical component towards the creation of an ISA, they would not be able to interpellate anyone without also possessing the societal power that grants them the ability to recruit people via interpellation. Essentially, an ISA is at its most effective when it contains both ideology and the power to broadcast their ideologies to a large population of subjects. According to Althusser, people are “[always already] subjects” because they cannot help but be subjected to the power of an ISA that interpellates them due to shared ideologies (85). We, as subjects, are drawn to ISAs that that broadcast ideologies that are similar to the ones we already believe in. Therefore, the relationship between subjects and ISAs is a cyclical one that is rooted in shared ideological beliefs. Which is why, as Althusser ardently asserts, that we cannot escape the interpellation of ISAs that are interpellating us because we inherently recognize and feel drawn to ISAs that contain ideologies that reflect the ones we believe in.

With the way ISAs operate in mind, we have to consider not only what types of people are being hailed by the literary canon ISA, but what ideologies are shared between the literary canon ISA and those being interpellated by it. In order to obtain a cohesive understanding of why the literary canon ISA is responsible for the lack of scholarly and professorial representation of fan studies, we must first examine the parameters for a genre to be deemed canonical. John Guillory notes that “works cannot become canonical unless they are seen to endorse the hegemonic or ideological values of social groups” while “noncanonical works can be seen to express values which are transgressive, subversive, and antihegemonic” (19-20). Meaning, if a genre or text reflects canonical ideologies, it is labeled as adhering to canonical parameters, and the texts and genres that fall outside of these qualifications are labeled as noncanonical. The problem with this taxonomic process, however, is twofold.

Firstly, it creates a rigid binary that leaves little room for nuance or hybridity. In the eyes of the canon, a text is either canonical or it is not, there is no in-between. A text either reflects canonical ideologies or it is trying to challenge them. The choice to label the texts that subvert canonical ideologies as noncanonical brings me to the second part of the problematic taxonomy enacted by the canon and its supporters. In her manifesto, glitch feminist Legacy Russell states that “we will always struggle to recognize ourselves if we continue to turn to the normative as a central reference point” and advocates for an eradication of the binary (28). Binaric systems enacted by a hegemony leaves no room for anything to remain in the in-between because of the hegemonic need categorize to avoid any semblance of rebellion. Furthermore, a binary only offers too categories: that which is normal and that which is not normal. Within this framework, what is not accepted is constantly being compared to and read against what is accepted, which is why everything that falls outside of canonical parameters is labeled as noncanonical. If we continue to perpetuate this process and classify popular genres as noncanonical, we are doing exactly what Russell is saying that people need to avoid: we are reading popular genres – like fan studies – against what is hegemonically labeled as “normal” or canonical. Fan studies has been and will continue to be found lacking in the eyes of the canon, so why is it continuing to be held against standards that are always going to see the genre as failing to comply to the canon’s ideologies? I want to return to my earlier point where I emphasized that this project is not a plea for the canon to recognize fan studies as a canonical genre. Within the scope of this project, fan fiction is going to remain in the glitch, in the in-between of the binary it has tried to be forced into by the canon because when something stands in the in-between, whether it be a text, a body, or a genre, it is “fail[ing] to be recognized and categorized by the normative hegemony of the mainstream” (67).

Placing fan studies in the in-between allows for us to understand its nuances and qualities away from the guise of the literary canon ISA and within what Fred Moten and Stefano Harney call the Undercommons. The Undercommons is essentially the antithesis of the University bureaucracy. It is the place “where the work gets done, where the work gets subverted, where the revolution is still black, still strong” (102). Those in the Undercommons find themselves there because of their failure to comply to the expectations of the University. I choose to view Russell’s concept of the glitch as firmly entrenched within Moten and Harney’s theory of the Undercommons because at its core, “the glitch is a form of refusal” (8). By refusing to comply with the canon’s generic expectations, fan studies resides in the in-between, in the glitch, in the Undercommons, where it is not being held against canonical genres and found lacking based on a set of outdated parameters that systemically exclude marginalized voices. Positioning fan studies within the taxonomic glitch of the in-between decenters the literary canon ISA and allows fan studies to be examined – critically, academically, and colloquially – independently. Such independence allows readers, scholars, and fans alike to immerse themselves within the genre and form their own feelings and interpretations instead of consuming the interpretations of the genre set forth by the canon ISA.

The meaning-making and interpretation processes are integral components to the foundation of fan studies because of the field’s prioritization of readers’ interpretations and affective experiences with fan texts. Before literary poststructuralism, the canon and the academy valued authorial meaning over reader interpretations and believed that there was a “correct” way to read and interpret a text. The relationship between the canon and the academy demonstrates not only demonstrates how the canon operates as an ISA, but why this relationship sustains a problematic cycle of exclusion. An ISA cannot operate without subjects, and subjects cannot operate without an ISA to prescribe to. ISAs rein subjects in with their shared ideologies and guide subjects on how to act according to those ideologies. It is an inherently symbiotic relationship: one cannot function properly without the other. Now, it is important to note that not every ISA is immediately detrimental. Without any subjects to transform their ideologies into societal practices, an ISA would not be able to enact any substantial change. The problem lies, however, in the power the people that are being interpellated by an ISA possess. To stress the crucial role power plays in the ISA and subject relation, Althusser asserts that “[n]o class can hold State power over a long period without at the same time exercising its hegemony over and in the Ideological State Apparatus” (81). Put another way, if those being interpellated by a certain ISA are in a position of power that allows them to have an immense societal influence, that same influence will bleed into the ideologies of whichever ISA they believe in. The hegemonic group obtains control over the ISAs ideologies and integrates them into the ideologies that they project onto members of society. So, in this case, the academy absorbs the ideologies of the literary canon ISA and use them to further their hegemonic reach.

The academy has a vast influence on pedagogy in primary, secondary, and higher education, but this project is concerned with higher education on the university level. More specifically, I want to draw attention to how the literary canon ISA provides the academy with tools to ensure that canonical ideals retain a firm presence in college English classrooms. With this is mind, I want to return to an earlier point regarding the academy’s projection of a “correct” interpretation of a text. The idea of a singular and proper interpretation that is meant to be universally applicable is just that: an idea. It is not feasible for there to be a single interpretation that is accepted by everyone because everyone’s interpretation of a text varies based on their interaction with it. Yet, until poststructuralism, this was common practice because of the long-standing premium the academy places on authorial meaning.

To provide an example for this concept, I will continue to use Lost analogies to contextualize these academic ideas within a pop culture framework. Imagine that there is a group of fans within the Lost fandom that are seen as the “leaders” amongst the other fans. Now imagine that that group of people’s interpretation of the show is projected as the correct way to interpret the show and all other dissenting interpretations will either be ignored or deemed to be incorrect and not worthy of consideration. Doesn’t this seem like a foolish and impossible task? Lost is notorious for being a show whose ending is open ended and up for interpretation. Fans come to a decision on the ending and the show as a whole depending on a variety of different factors like what characters they relate to and why and which plot line was their favorite. We, as fans, as Nicolle Lamerichs notes, are “excessively affected by existing material,” and entrenched within what Louisa Stein calls a “culture of feels” (18-19). Being a fan is being deeply connected to the affective and emotional experience when engaging with fan texts. I mention this to emphasize the personal stakes many fans have within their fandom or fan object. Given the affective presence within the meaning-making process, it does not make sense for the “leaders” of the Lost fandom to project their agreed upon interpretation as correct, and the same can be said for the academy.

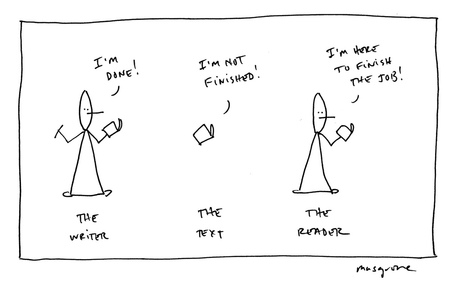

The notion of there being a “correct” way to interpret a text creates a binary with misreading at the opposite end of the spectrum. Misreading encompasses the interpretations that do not adhere to the canon and the academy’s parameters for a “correct” interpretation. Misreading houses all the subversive, the challenging, and the counterhegemonic readings that deviate from authorial meaning and question the validity and credence of the canon and the academy. Binaries, Russell stresses, leave no room for the in-between. In the eyes of the academy, there are interpretations that match authorial meaning and those that do not, and those that do not are denigrated within academic discourse. Fan studies, then, would be placed firmly within the misreading side of the binary because how much the field values readers’ interpretations. Fan studies advocates for readers to create their own interpretations even if it deviates from what the author has presented to them, but they do so without eschewing the author from the meaning-making process entirely. The reader, the author, and the fan text are all crucial towards obtaining a cohesive interpretation of a specific text, and fans often utilize Wolfgang Iser’s reader-response theory when engaging with a text.

Central to Iser’s reader-response theory is that texts and their interpretations are inherently ascertainable. This is a direct challenge to the structuralist and canonical belief set forth by the academy that there is a “correct” interpretation to make about a text, and Iser stresses that “it is the very lack of ascertainability and defined intention that brings about the text-reader interaction” (1454). Iser advocates for an interpretive process that considers the reader, the author, and the text itself, since he believes that only when each component is considered, can a thorough interpretation be made. A tenet of Iser’s theory is that readers fabricate their interpretations based on what is implicitly omitted rather than what is explicitly stated. Authorial intent – or what is explicitly stated within the text – only serves as part of the foundation for the interpretive process, though, because Iser’s theory of the blanks within “the fictional text induces and guides the reader’s constitutive activity” during the meaning-making process (1459). The blanks within a text are of paramount importance because these vacancies allow readers to take pause, to reflect on everything they have absorbed from the text thus far and shift themes into the foreground or cast them into the background while they decide which ones fit within the interpretation they are creating. Furthermore, the pause a reader takes when firmly positioned within the textual blanks are where the reader uses their lived experiences and their personal values and ideologies and imbues them with their interpretation of the text they are interacting with. Iser’s concept of the text and reader interaction stresses that the interpretive process is innately personal, much like Lamerichs says regarding the intrinsically affective experience of being a fan.

Iser’s reader-response theory and text and reader interaction makes clear that the concept of misreading is weaponized by the literary canon ISA and its academic perpetuators. It is not possible for there to be a universal interpretation that every person who engages with a specific text is going to agree with because of the personal stakes a reader has within the interpretive process. Why, then, does the academy perceive interpretation singularly when it is nuanced and multitudinous, and suppress any voice, text, or interpretation that deviates from their parameters for what a person is meant to take away from a text? I argue that the academy enacts this practice in an attempt to retain some semblance of control over the canon’s now unstable hegemonic position in the current literary landscape. While the canon once held a firm, almost immovable position of power within literary discourse, the literary canon ISA finds itself less assured in this newfound landscape where popular genres – like fan studies – have a much larger presence than the canon is comfortable with.

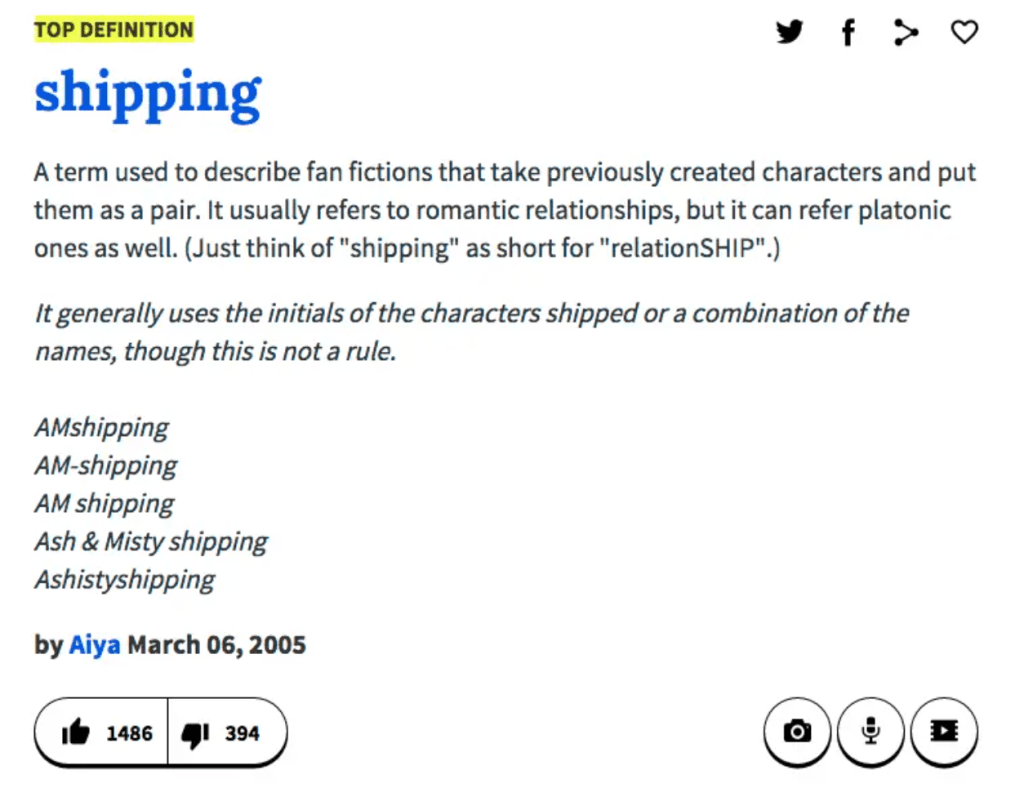

Despite the increase of academics, critics, popular readers, and scholars gradually beginning to decenter the literary canon ISA from the heart of literary discourse, its continues to affect the composition of syllabi across all levels of education. Extricating the literary canon ISAs ideologies from literary discourse and pedagogy is a complex and lengthy process, but change does not need to occur on a large-scale to yield results. I argue that eschewing misreading as a practice in classrooms will instill students of all ages with the confidence to create their own textual interpretations and embody Iser’s concept of the reader-text relationship. Misreading does not need to be absent from classrooms entirely, though. Instead of using it to enforce a binary that leaves no room for nuance, it can be used to educate students on the relationship between ISAs, power, and subjects. For example, misreading can be used to demonstrate that how much power a subject or a group of subjects holds influences whether the ideologies within a specific ISA are going to have positive or negative consequences when integrated into society. If we continue to present the interpretive process as a binary, it will, as Henry Jenkins notes, “preserve the traditional hierarchy bestowing privileged status to authorial meanings over reader’s meanings” and “implies that the scholar, not the popular reader, is in the position adjudicate claims about textual meanings” (29). Remaining on the outskirts of canonical consideration allows fan studies and all who engage with fandom to exist in the in-between. This, Russell emphasizes, makes them a direct threat to hegemonic order because of their adamant refusal to be categorized or adhere to canonical standards. Fan studies is filled with jargon that is unrecognizable to those who do not engage with fandom, which is why I included a self-defined glossary that includes some of the most prominent terms used within the field. To those unfamiliar with fan studies and fandom, these terms are going to appear nonsensical because of the vast cultural and colloquial knowledge needed to understand the terms in context. Fan studies, via Russell’s concept of glitch encryption, use their jargon to protect their feelings, interpretations, texts, and community from hegemonic hypervisibility. This encoding process “creates secure passageways for radical production” within the field and asserts that fan studies does not need to be labeled as canonical for it to have an impact on both society and literature (85). The affective experience is at the heart of fan studies, and this “radical passion and passivity” renders fan studies “unfit for subjection” by the literary canon ISA (Moten and Harney 103).

The intentions and goals for this project that I stated in the beginning are just that: my intentions. Each person who interacts with this project is going to take away something different, even if it deviates from what I have set forth. I want dissenting opinions. I want readers to latch onto the many different topics discussed in this project and have it spark their interest enough to research the topics further on their own volition. The only consistent hope I have for all who engage with this project is that you can feel the passion behind its creation. I love reading and I love who my time spent in collegiate English classes has helped me become, and I want to bestow the same confidence and passion onto anyone who takes the time to scroll through this project. Everyone deserves to know themselves and I have been lucky enough to be given a space that helped me along the journey of self-discovery. This project is my love letter to fan studies and literature pedagogy alike because, as I hopefully demonstrated, when we exist within the glitch and accept variation and nuance, we create a space where everyone has a stake and where every voice is heard, respected, and valued.

Leave a comment